Writing about energy is an oddly exhilarating experience. Sure, in the current global state of energy affairs, the topic can be a lightning rod for kooks and very angry people on the internet, but the flip side is also true: it opens the door to a great many new and interesting people.

A consequence of these introductions is another positivity; encountering people who genuinely want a better understanding of energy, with no axe to grind either way, people who are far outside the industry but curious as to what they read online is true or not. What emerges from those people are often excellent conversations and an opportunity to explain nuances that are not present in mainstream ‘acceptable narratives’ or the inevitable follow-on shouting matches in comments sections.

One sad aspect of these conversations though is the sobering reality of how far people’s understanding is from reality, or just how captured it is by stereotypes. One example was a woman I met at a wedding in Ontario who, when asking about oil production, literally thought that a well could be drilled anywhere in the province and oil would automatically appear. Another, a guy from Montreal, was astonished to visit the west for the first time and see that it was not an endless industrial hellscape covered in abandoned pump jacks and oil stained earth, but that the hydrocarbon industry is but a tiny fraction of the landscape pretty much anywhere outside of refinery row (and even that is an impressive sight, cranking out all that fuel for western Canadians). I interrogated each of those people somewhat to determine the level of exaggeration in those preconceived notions, and while there was a little, those were genuine anchoring viewpoints that formed a general impression.

Luckily, those examples are fairly easy to calmly and successfully set straight. To write about energy continuously means keeping up to date with as much current information as possible. So general cartoonish misconceptions aren’t that hard to work through. Unfortunately though, for concept of general energy literacy, the challenge is much, much harder. Over-simplified topics require nuance and numbers to clarify the overarching value of certain alternatives in the energy world, both absolutely and relative to each other, particularly when people genuinely want things to be better environmentally.

Here’s one example, a comparison of natural gas scavenged from landfill sites compared to drilling natural gas wells. At face value, and with no context, who wouldn’t want to see landfill gas be utilized first and foremost? At face value, everyone would, because it is a cool idea and a great use of a byproduct of waste. But let’s look beyond face value, and then consider the challenges of explaining the whole story, in an era when 20 seconds is considered a long time to hold one’s attention.

A company called Waste Management (WM) constructed a renewable natural gas (RNG) facility, the Fairness Complex, in Pennsylvania a few years ago. The facility scavenges landfill gas from 3 landfill sites, funnels it to a central processing facility, and produces about 3 million MMBTUs per year. WM says this is enough gas to power 63,000 homes, which is a lot more than my Canadian home conversion rate, but hey maybe they consume a lot less over there. Anyway, what does 3 million MMBTUs per year mean…converting to familiar ground, at a 40 GJ/e3m3 heat rate that works out to about 7.7 million cubic feet per day.

This Fairness Complex will save about 170,000 tonnes of CO2e per year over a period of about 20 years. The methane generating capacity depletes about 3-5 percent per year (as per this Motor Week profile), and after the 20 year expected life the facility will be decommissioned. The facility cost about $90 million US and covers about a city block. By then the production will have declined to less than half of original rate, and WM expects that new sites will be found to replace this supply.

Meanwhile, about 50 miles north of the Fairness Complex, in the dry gas NE Pennsylvania Marcellus, producers routinely drills wells that come on line at rates 4-6 times that rate – some Expand Energy wells come on production at 50 million cubic feet per day. The wells do have very steep decline rates in the first year, but production levels flatten out and remain significant for decades. Such a Marcellus well would cost about $8 million.

In one county in NE Pennsylvania, Susquehanna County, there are 50 well pads that have each produced more than 80 BCF of gas to date, or more than twice what Fairness is expected to produce in its lifetime. There is infill drilling on these pads for decades. The quality of wells will fall over time, and decline rates are staggering, but even then the poorer wells will still produce more gas than the $90 million Fairness complex.

This isn’t the slam against RNG that it sounds like, which is part of the problem in public discourse. This is a cost/benefit analysis, but in certain very agitated circles, the polarization sweeps everything aside in its path. To defend hydrocarbons means an alignment with one element of the political spectrum which means guilt by association for anything on that side of the fence. One wrong word and you’re branded as a Nazi. Not everyone is like that; people that earnestly study subjects are most interested in this sort of discussion. But what percentage of voters does that sound like? I’ll tell you: three. The rest get their news from Facebook or Twitter or Instagram or TikTok. If you don’t believe me I have two words for you: Charlie Kirk.

But looking beyond howling ideological mobs, the Fairness case study (relative to Marcellus gas) highlight two things: the immense value of existing infrastructure, and the perhaps pointlessness of expecting the concept of true ‘energy literacy’ to ever spread beyond energy gear heads.

Let’s talk about infrastructure first, because it is the key to any large-scale energy policy discussion. We are where we are, as humanity, because of hydrocarbons. Peter Zeihan put it simply and correctly: “Oil is civilization.” A century ago, the rate of industrialization was tied to access to hydrocarbons (and a governing framework that allowed enterprise development). Over that century, an unbelievably large infrastructure base was constructed, bit by bit, to stabilize and expand that global hydrocarbon web. Starting from the base: huge oilfield development; pipeline systems; tankers and tank on/offloading facilities; oil refineries and gas processing plants; pipe and truck distribution systems; fuel stations; home heating systems; countless ancillary businesses built on this infrastructure.

That is why a Marcellus gas well can deliver five or seven times the gas rate as three landfills for ten percent of the cost. It is an absolute dead weight loss to society to refuse to maximize that existing infrastructure first. Note precisely what that says: there is no dismissal of new technologies, RNG, any of that, but the transition to anything else should logically happen when the utility of existing infrastructure has been maximized and is declining relative to new. RNG can make perfect sense if used to power otherwise isolated landfill sites, where the cost of say building natural gas pipelines and infrastructure is cost prohibitive.

That’s the kind of great conversation one can have, if the parties understand the lay of the land, of economic realities, and of local or comparative advantage.

Then comes the depressing aspect of what the Fairness example shows about energy literacy. Y’all are reading the BOE Report, so are presumably energy aficionados, meaning you understand energy to some extent or at the very least are interested in the topic.

And yet most of even this energy-sophisticated crowd – come on, admit it – start losing interest halfway through that blizzard of statistics and energy unit conversion footnotes and decline rates and blah blah blah. I bored myself just writing it.

And yet that is the level of analysis required to get people to truly understand the significance to society cost-wise by choosing a wildly inefficient method of burning the exact same fuel over an efficient one. To understand the pros and cons, it is necessary to weigh into this level of boring detail, and that is often a losing proposition to emotional arguments about whether grandchildren will survive if more gas wells are drilled.

Even if one has the energy to try to explain the cold hard logic to an audience of one option versus the other, where is the venue to do that? Where would you find a platform that JQ Public inhabits that would facilitate that? TikTok? Sure, boil it all down to 12 seconds of rapid-fire images before bored youth scroll on? Facebook? Home of shrieking Karens and pictures of barbecued pork chops and I don’t know what else because I dropped it years ago? The hellscape that is Twitter/X? Which can be a wonderful place if extremely carefully curated content wise, but will fall right off the rails if tacking a topic such as Marcellus vs. Fairness?

I lamented this to someone recently, the fact that widespread energy literacy seems like such an impossible goal. But possibly the problem is that I can’t see the solution, and that there are ones available. This person said that a group was working on an energy literacy campaign and was starting with teachers and professors. That is an excellent idea; the classroom is a fantastic forum in which to explore such debates. The embedded animosity in some disciplines may be too much to overcome, but what else is knew: Marxists have had a foothold in the halls of academia for a very long time, and students have found ways to work around that plague.

Maybe that is an important ray of light also. Students may tend towards nihilism, it seems, based on the average TikTok feed anyway, but it probably isn’t nihilism at root but more of a distrust of either propaganda or decades of bad leadership. In the good old Soviet days, propaganda was the norm, and to say anything different was to invite time in prison. Now, thankfully, we live in a quite-free society, one where propaganda quickly becomes the feedstock of clever meme artists. There isn’t much strong evidence of universal disrespect as a true nihilist might display, more of a selective grade with possibly healthy skepticism.

Reality will win out in the end. The infrastructure the world has build is simply irreplaceable in any visible timeframe, and maybe that’s how true energy education goes – a too-close encounter with energy scarcity will draw attention very quickly. It could happen via other avenues as well – Trump’s anti-Canada rhetoric has led to an astonishing rise in support for oil and gas pipelines, right across the country. And people are definitely becoming more aware of just how vital reliable and affordable energy is to everything we enjoy on a daily basis.

That newfound voter-vision may well be buttressed soon by the very public display we’re about to see relating to how hard it is to build any infrastructure. The federal government has gone all out on saying it will build infrastructure quickly; now we shall see. But at least voters are now cognizant of the value of existing hardware, and, however we got here, that’s a good thing.

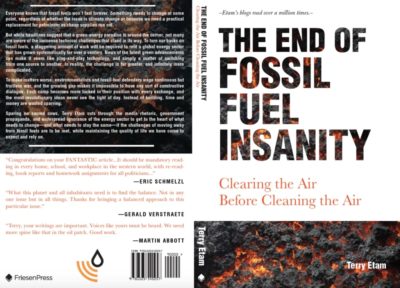

At the peak of the energy wars, The End of Fossil Fuel Insanity challenged the narrative, facing into the storm. Read the energy story for those that don’t live in the energy world, but want to find out. And laugh. Available at Amazon.ca, Indigo.ca, or Amazon.com.

Email Terry here. (His personal energy site, Public Energy Number One, is on hiatus until there are more hours in the day.)