For more than a decade, cheap energy has been one of the underappreciated pillars of U.S. economic and stock market strength. Since the shale revolution around 2010, the discovery and rapid scaling of unconventional oil and natural gas transformed America’s energy landscape. Not only did it reshape geopolitics, but it also provided U.S. companies with a durable cost advantage that helped propel record profit margins and equity valuations.

The question now is whether that “miracle” of cheap energy is nearing its limits—and what happens to corporate America if it does.

Shale, abundance, and the American cost edge

The numbers are stark. After 2010, the United States vaulted into position as the world’s leading producer of both oil and natural gas. By 2018, it had overtaken Saudi Arabia in petroleum production, and in 2020, the U.S. became a net exporter of petroleum for the first time in modern history. Natural gas, once scarce and expensive, turned into an abundant and cheap domestic resource.

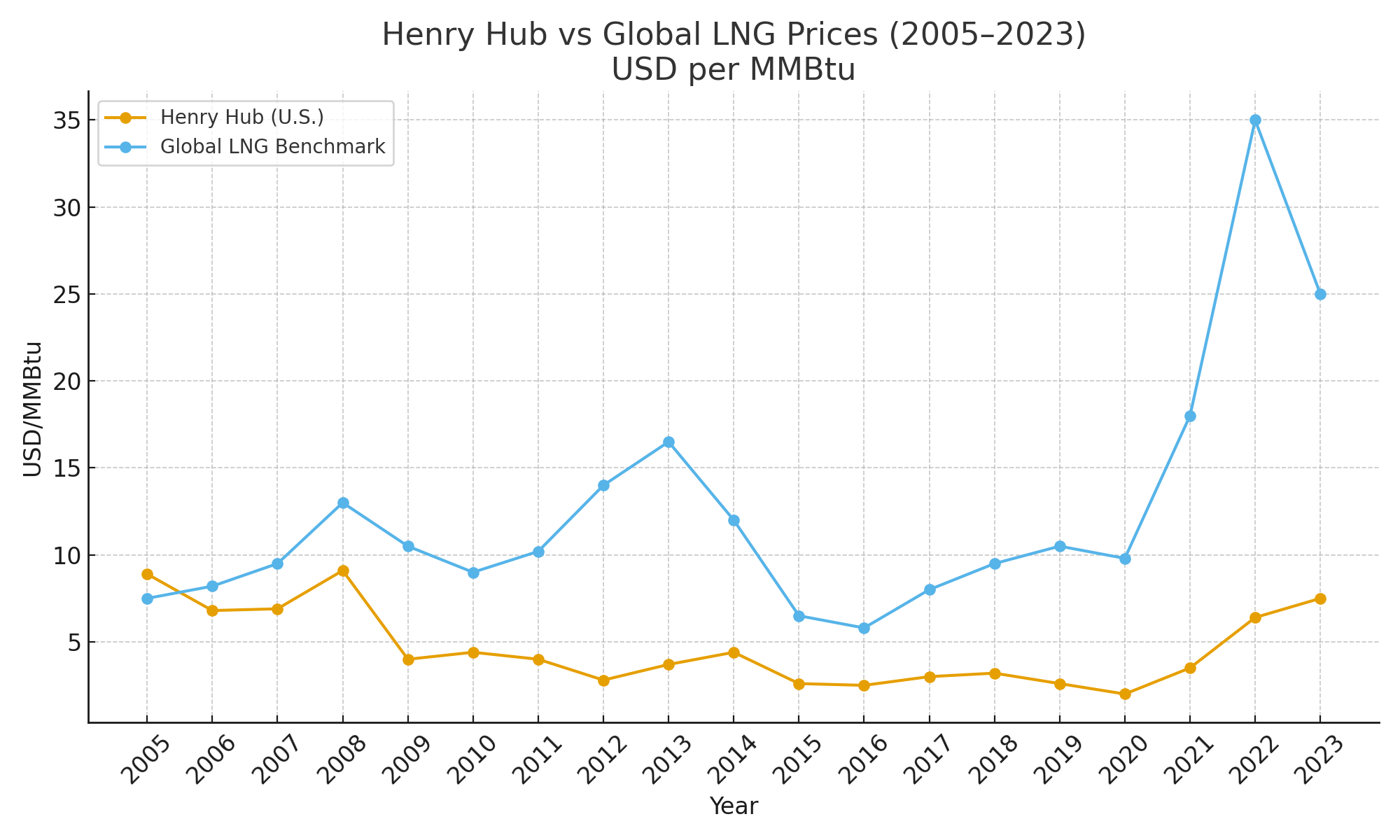

Henry Hub prices averaged barely $2–$3 per MMBtu through much of the 2010s—levels unthinkably low compared with prior decades and dramatically below Europe or Asia. As the chart below shows, the gap between U.S. benchmark prices and global LNG soared after 2010, with U.S. gas often less than a third of the price overseas.

That cost gap had profound industrial consequences. Energy-intensive industries—from petrochemicals to metals—flocked to the U.S., investing hundreds of billions in new plants and capacity expansions. Even sectors like airlines and logistics benefited directly from more stable, affordable fuel inputs.

Energy and the stock market: hidden leverage

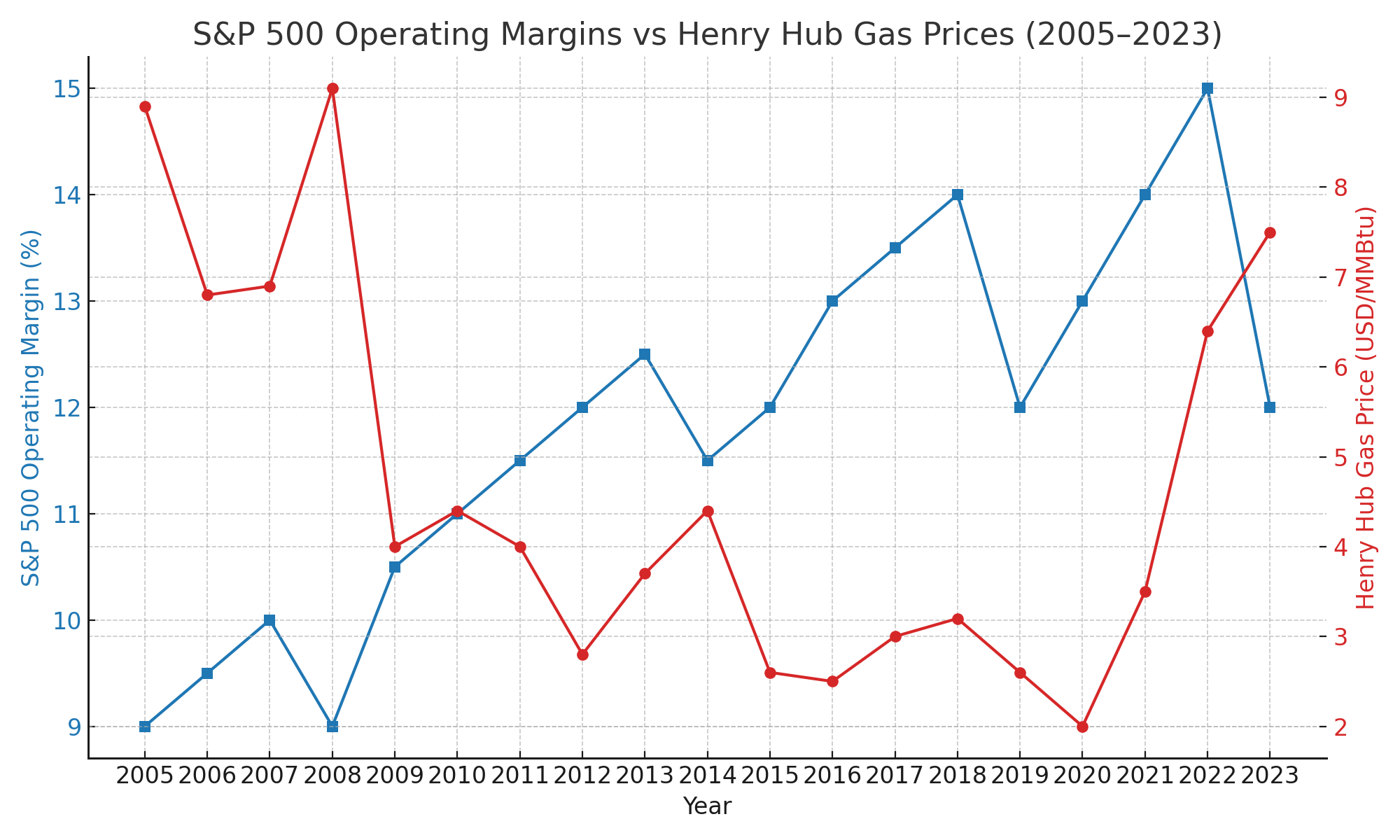

While technology and low interest rates often grab headlines as the key drivers of the S&P 500’s performance, cheap energy quietly supported the expansion of corporate profit margins.

Operating margins across the S&P 500 rose steadily through the 2010s, peaking well above historical norms. Lower energy costs acted as a silent tailwind—keeping inflation in check, freeing up disposable income, and reducing input volatility.

The relationship is visible in the chart below: as natural gas prices trended downward, corporate margins trended upward at or near record highs.

Airlines, for example, typically spend about 30% of their costs on jet fuel. For manufacturers and data centers, electricity is a major operating expense. Lower, more predictable energy costs meant higher profits—and higher valuations.

The AI decade: rising demand, rising risks

But the equation may be changing. A wave of new demand—from AI-driven data centers, electric vehicles, and industrial reshoring—is straining the U.S. grid. The International Energy Agency projects U.S. data centers alone could account for nearly half of electricity-demand growth through 2030. Utilities and regulators are already warning of bottlenecks, capacity shortfalls, and the need for massive new investment in generation and transmission.

If energy costs rise structurally, corporate America faces a very different landscape:

-

Margin compression in energy-intensive industries, as power and fuel costs creep higher.

-

Regional winners and losers, with areas that can provide abundant, scalable, low-cost energy (think Western Canadian and Texas gas, Gulf Coast petrochemicals, or hydro/nuclear-rich basins) attracting outsized investment.

-

A utility and infrastructure boom, as capital flows into new generation, transmission lines, and storage technologies.

-

The “safe, secure, and cheap” race, will point to those established energy companies that can provide stable, low-cost energy to a power hungry world, while nuclear, long-duration storage, and advanced geothermal look for technological breakthroughs to potentially become an additional source of reliable energy.

What if cheap energy ends?

The miracle of cheap shale energy gave the U.S. a decade-long cost advantage that rippled across industries and helped lift stock valuations. But miracles don’t last forever. If electricity prices climb steadily in the 2020s, the S&P 500 may find its margins capped, and capital could rotate toward firms and regions that secure and provide their own stable energy supply.

In other words: the next decade of market leadership may depend less on software and more on safe, reliable and cheap energy supply in a world that is always in need of more.